A Stanford Neuroscientist is Working to Create Wireless Cyborg Eyes for the Blind

Meet the man who is making a new kind of brain-computer interface.

Seeing The Light

For the nearly two million Americans who have degenerative eye conditions, the ability to see is anything but a guarantee. Although we can slow the progression of vision loss—for example, patients can take special vitamins for the disease—there is no cure. And once it’s lost, vision can’t be restored.

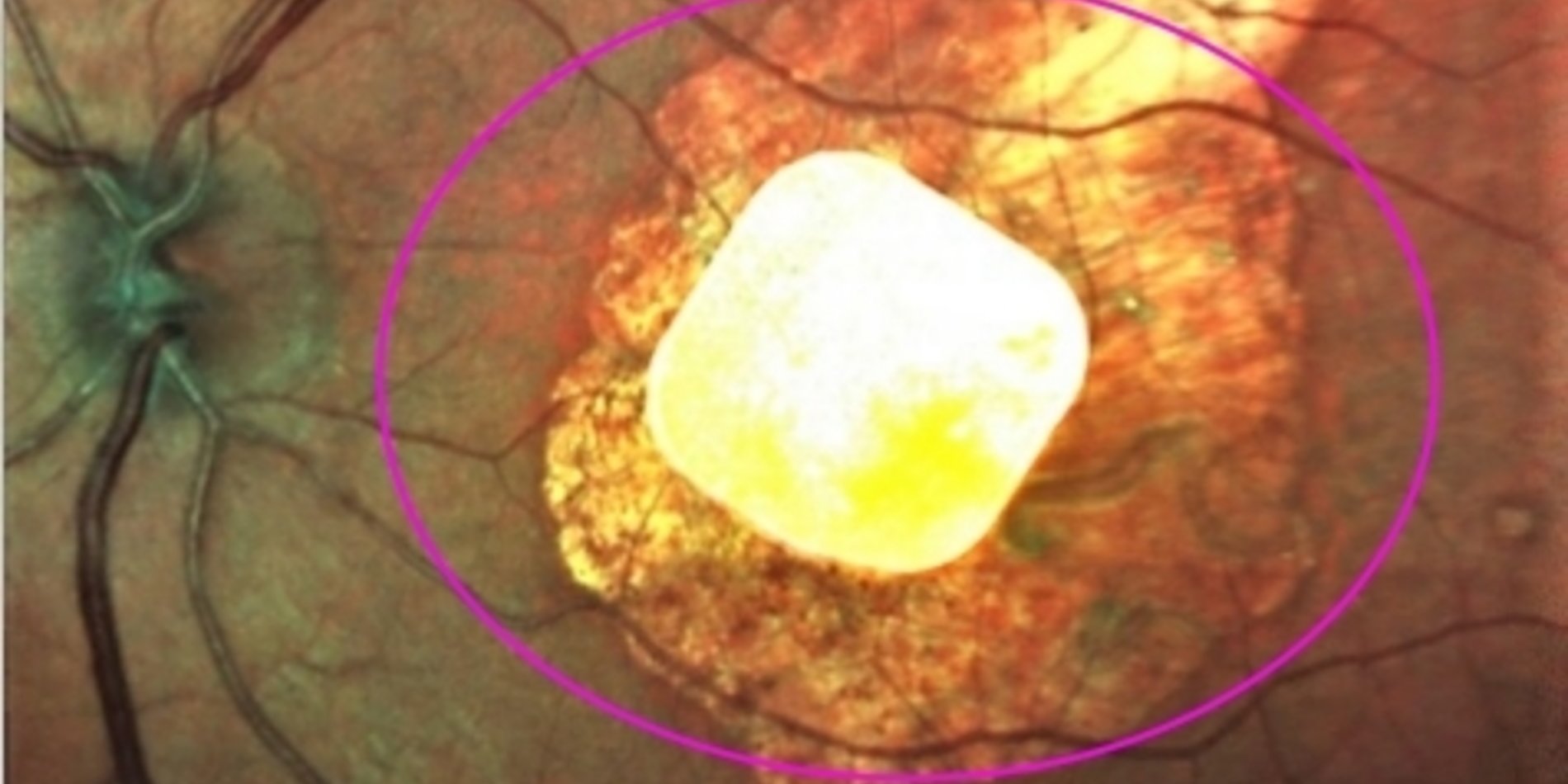

Two of the most notable conditions, retinitis pigmentosa and age-related macular degeneration (AMD), cause cells on the retina, which is the region at the back of the eye that converts light into electrical signals, to die off. As a result, those afflicted with the diseases lose their sight as they get older. Thus, these conditions are of increasing concern, given our growing aging population.

Fortunately, a futuristic solution is on the horizon. And it has to do with becoming cyborg.

In the past few years, some patients have been fortunate enough to get devices implanted on their retinas to help them see again. Unfortunately, these devices aren’t very good, only illuminating blotches of light and dark, devoid of details. Alos, they’re expensive, costing patients upwards of $150,000. To some, that’s better than nothing. “I understand that I will not have 20/20 vision and that I won’t be able to distinguish faces. But at least I will be able to know that my grandchildren are running across the yard or walking into my house,” one recipient told the University of Michigan in 2014.

But E.J. Chichilnisky, a professor of neurosurgery and ophthalmology at the Stanford University School of Medicine, has a much grander vision for retinal implants. To fulfill it, he plans to create a device that revolutionizes the way electronic devices interface with the brain.

A Dialogue With The Retina

To break down the issue a bit more, in a healthy eye, light passes through the cornea and lens, entering the eye through the pupil. That light then falls on the retina, where a series of different cells turn light into electrical signals that are then transmitted into the brain via the optic nerve.

As previously noted, retinitis pigmentosa and AMD cause many of the cells in the retina to die, so the signals that transmit visual information are stopped before they can reach the brain. Current retinal implants simply take the place of those dead cells, turning light into electric signals.

But the disease doesn’t kill all cells in the retina—and this is where the problems arise with current implants.

Retinal ganglion cells, which pull in information from all the other cells in the retina, seem to survive the culling. There are about 20 different types of retinal ganglion cells scattered across the retina, each of which transmits a different type of information to the brain.

Timing is essential to the function of these cells. One type of cell could tell the brain a region on the image is brighter now than it was a moment ago, and another could tell the brain the image is darker. If both are activated at once, “that’s a nonsense signal sent to the brain,” Chichilnisky says.

That’s part of the reason current retinal implants are so limited. As Chichilnisky notes, they ignore the functioning retinal ganglion cells, activating them all at once. “Vision is like an orchestra trying to play a symphony. It depends on having [the right signals] at the right time and right place,” Chichilnisky tells Futurism. “If you instruct all the instruments to play indiscriminately, someone will hear you. But it’s not music.”

Chichilnisky aims to get each type of ganglion cell, each “instrument,” to play at its proper moment. Eventually, his team’s so-called smart prostheses will be surgically implanted into patients’ eyes and be powered wirelessly, probably from a pair of specialized glasses that the patient would wear.

But they’ve got to do a lot to get there. Getting the right signal to the right cell at the right time is difficult because the mixture of different types of ganglion cells varies between individuals and may even change over time, Chichilnisky says.

Chichilnisky’s solution is to create a device that can not only transmit the right signals to the ganglion cells, but also read the retina to figure out which kind of ganglion cell sits where. Then, the device can stimulate it at the right time to create a cohesive image. “It’s a dialogue with the retina—you have to talk back and forth to the circuit,” he notes. He envisions that the final version of the device will “write” all the time, but “read” the retina only occasionally.

But there are other technical challenges. The device has to be made of the right material so that it can stay on the retina for long periods of time without damaging it or sparking an immune response. It also demands a dense concentration of fine-grained electrodes on a small chip that doesn’t emit too much heat. “We have to take everything we know and program it effectively into chip that can sense its environment, figure out what’s going on, and do the right thing at right time in the right place, always. And it has to be smart enough to talk to a neural circuit,” Chichilnisky says. “It’s a tall order.”

A Bright Future

Chichilnisky’s team, made up of neuroscientists, circuit designers, and an eye surgeon, is still figuring out the exact design of their device. Currently, the researchers are testing different techniques on the excised retinas of animals used for other experiments. To perform all the tasks that their compact device will eventually perform, they need an entire room full of scientific equipment. They plan to reduce all this to a small implanted chip.

But this isn’t the only team in the game.

Other scientists are working to restore vision in patients with retinitis pigmentosa and AMD, and already, tests of gene therapy and stem cell therapy techniques have produced interesting results. But Chichilnisky isn’t worried. “I’ll be thrilled if someone comes along and cures AMD while we’re doing this stuff,” he says.

This is because Chichilnisky believes that, regardless of what other developments in treating blindness come about, the technology he is developing will represent the future of neural implants, as their utility extends far beyond just sight. Devices that can both listen and talk to the brain in the same “language” will enable humans to treat neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s or control prosthetic limbs.

The same tech will likely be used to hack our own biology, augmenting our memory and pushing our vision to new limits. “It’s going to happen. If you think it won’t, you haven’t been reading enough,” Chichilnisky says. According to him, the retina—one of the best-understood and most accessible avenues to the brain—is only the beginning.

Chichilnisky hopes to have a lab prototype in the next couple of years and to start testing it on live animals within five years. Predicting when such a device could be tested in humans, to say nothing of when it could be widely available, becomes murkier. But he hopes that human studies could happen within the next decade.

Though the technology is still at too early a stage to spin off into a company and seek investors, Chichilnisky has no doubt that many will be interested…and soon. “The thing I’m talking about is a revolution,” he says. And we are fortunate enough to be here to witness the start of it all.